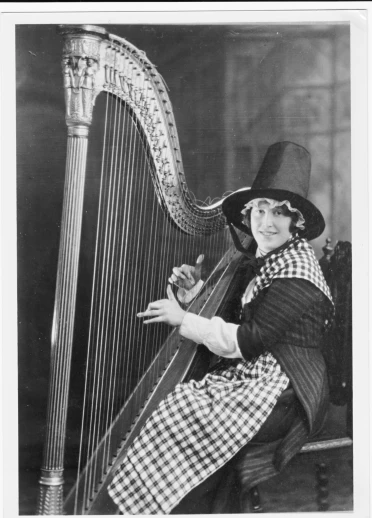

Long associated with schoolchildren in St David’s Day parades, folk dancers, and ceremonial celebrations of Welsh heritage, the het Gymreig has often been seen as a costume rather than everyday wear - until now.

Though it hasn’t (yet) returned to mainstream fashion, the hat is enjoying renewed life as a bold cultural and artistic emblem. In recent years, a growing number of creatives have adopted this tall, stovepipe-style accessory to express a modern sense of Welshness - one rooted in history but alive with new meaning.

So what has inspired this revival?

From rural workwear to fashion statement

The distinctive form of the Welsh women’s hat emerged around the 1830s, becoming an iconic element of traditional Welsh dress. Before that, rural women often wore practical felt hats - typically adapted from men’s styles - resembling bowler hats or lower-crowned versions of the stovepipe silhouette we know today.

Some historians trace the hat’s origins to late 18th-century riding hats worn by women, which also featured high crowns and broad brims, while others point to influences from contemporary English and European fashion, particularly men’s top hats, which were reimagined through a distinctly Welsh lens.

As interest in preserving the Welsh language, customs, and dress intensified during the 19th-century cultural revival, the Welsh hat became a potent symbol of national identity - one worn with pride, particularly on formal and ceremonial occasions.

A symbol of identity and collective power

While the het Gymreig rose to prominence in the 1830s, its symbolic power was already being shaped much earlier. One of the most enduring stories is that of Jemima Nicholas - Jemima Fawr (Jemima the Great) - a Fishguard cobbler credited with capturing 12 French soldiers during the 1797 invasion of Wales. According to legend, she rallied local women to wear red shawls and tall black hats, mimicking the look of British soldiers from a distance and contributing to the enemy’s surrender.

A few decades later, the hat was again tied to resistance. During the Rebecca Riots (1839–1843), male protesters fighting against unjust tolls and social conditions disguised themselves in women's clothing - including tall black hats. Known as Merched Beca (Rebecca’s Daughters), they used the attire to conceal their identities and draw on folk traditions. In their hands, the hat became a tool of protest and collective power.

Modern revival: From folk stage to subversive style

Today, the het Gymreig is being reinterpreted with fresh style and purpose, with a number of contemporary Welsh musicians and performers are embracing the hat as part of their identity.

Welsh folk band, NoGood Boyo, has made the hat a signature part of their look - combining it with balaclavas, sunglasses, and streetwear, they’ve injected new vitality into a once-static emblem to create a visual statement that is playful and political. Their performances fuse tradition, satire, and gender commentary, nodding to figures like the Merched Beca, while challenging outdated images of Welshness. For them, the hat is more than a historical costume; it’s a symbol to be remixed and reclaimed.

A role in contemporary art

Beyond music, the hat is being embraced in queer and feminist art spaces as a means of reimagining Welsh identity. In Qwerin, a contemporary dance project by choreographer Osian Meilir, dancers wear tall black hats - sometimes altered with cut-out eyeholes - transforming them into emblems of queerness, anonymity, and resistance. Blending folk tradition with subversive movement and visuals, Qwerin challenges narrow ideas of gender, identity, and the cultural belonging of traditional Welsh dress.

Visual artists are also redefining the hat’s significance. Seren Morgan Jones paints strong female figures in traditional Welsh attire, presenting Welsh women as powerful and unyielding.

Meanwhile, Meinir Mathias brings a modern twist: in her bold oil paintings and artwork, the het Gymreig appears on men as well as women, often styled with earrings and contemporary fashion. Her art recasts the hat as something proudly Welsh but also fluid, current, and inclusive.

What comes next?

As the Welsh women’s football team heads to the Euros in Switzerland this summer, questions arise: could the het Gymreig become a unifying national symbol once again - not only in art and folklore, but on an international stage?

What’s clear is that the hat is no longer just a relic of the past. Whether worn in satire or sincerity, in protest or performance, it now carries fresh weight. Its tall silhouette, once seen as quaint or costume-like, is being reclaimed as a bold expression of modern Welshness: unapologetically proud, wonderfully peculiar, and open to reinvention.