I’d like to take you on a pub crawl (yes, a pub crawl) through the county of Gwynedd, in North West Wales.

It’s going to be a four-stop affair, arriving at four separate villages; Llandwrog, Llanystumdwy, Llithfaen and Nefyn. Each one has a fabulous pub - I wouldn’t take you otherwise! Our designated driver informs us that it’s a total trip of 25 miles; on average, a 15-minute ride between each call. With tremendous sea-to-mountain views all the way.

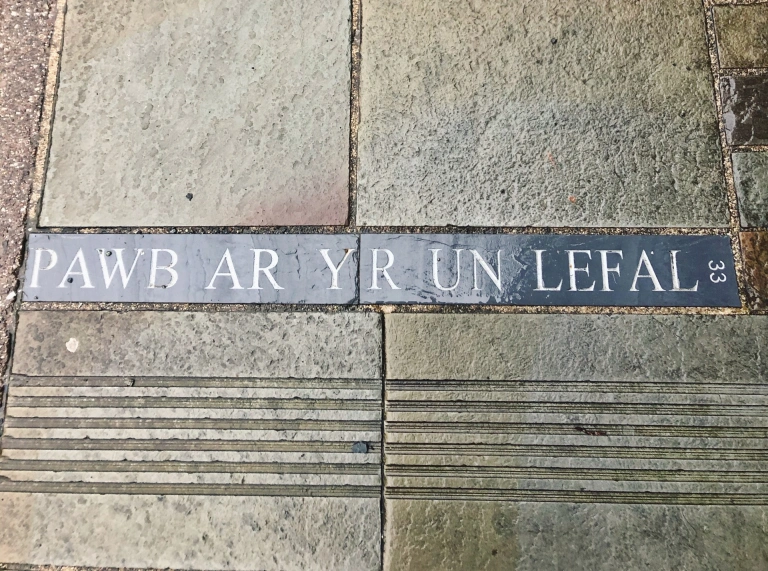

All of these villages have a few things in common. None have more than around 2,500 inhabitants. All are in the Welsh-speaking heartland of Wales. All are also located in some of the most rural communities in the UK.

Saving the heart of the community

Let’s head into the inns themselves. Here, as we chat to the locals and sample some outstanding Welsh ale, we learn something else. In recent years, all four pubs were faced with closure (if they hadn’t already shut up shop).

And then, something remarkable happened. In all four villages, the residents rallied. Determined not to let the heartbeat of their community disappear, they mobilised. They arranged public meetings; set up fundraising committees; formed business plans; recruited volunteers. They got campaigns going on social media.

Sometimes, they looked for grants. Mostly, however, they amassed funds by offering prospective shares at low prices to the public. All campaigns somehow found the necessary capital to purchase these historical taverns and drag them positively into co-operative ownership.

Today, they’re all social enterprises; pubs bought by local people, run by local people. And it has happened four times within a tiny radius of eight miles deep in the North West Wales countryside.

Dr Debbie Humphry, Oxford Brookes UniversityThe regeneration of place meant the regeneration of communities and the regeneration of hope."

Miriam Trefor, from the committee that runs Tafarn y Plu ("The Feathers Inn") in Llanystumdwy, tells us what drove them.

‘We were determined to keep a historical building in local ownership. But the biggest factor in our campaign to purchase the pub was the fact that it was the village’s sole social hub. Losing it as a resource would have been an immense blow to the village’s sense of community and culture. We also wanted to sustain jobs for local people, and support local suppliers and business. That has all been realised.’

In each of the pubs that we visit, the account is extraordinarily similar.

‘I think it's important as a local community that someone can be part of something,’ says Bleddyn Evans from Yr Heliwr ("The Sportsman") in Nefyn. The main street’s main drinking den had been closed for four years before local citizens stepped in to bring it back to life.

As we embark on our bar-hop, we’ll notice another striking feature. These inns may be traditional watering holes in appearance; you can feel the history seeping from their beams. But they’ve also taken it upon themselves to serve the community at large in a manner that goes way beyond pints and pitchers. They’re the embodiment of the "pub is the hub" movement, offering for local people vital services and activities that would otherwise be missing. Throughout the week, they cater for residents of all ages and backgrounds.

Bleddyn Evans, Yr Heliwr, NefynThe pub was on the market. "Why don't we try to buy the local pub", we thought. Things have gone from strength to strength. There's no doubt that this is the way forward for every village."

Creating vibrant new opportunities

Next morning, let’s presume our excursions have left us a little worse for wear. We need fresh air, and head to the mists of Blaenau Ffestiniog, some 20 miles to the south. The town, which has a population of three thousand, is shrouded in a former slate mining valley. The nearby Oakeley mine was once the largest on earth. Today, though, the post-industrial blues can be witnessed literally in the heaps of discarded slate all around. However, Blaenau Ffestiniog is also the town with the most social enterprises per capita in the whole of Wales.

Out in the wider valley, we’ll come across a network of 15 vibrant not-for-profit businesses, all run under the banner of Cwmni Bro Ffestiniog ("The Ffestiniog Valley Company"). They include a hotel, a bike park, a health centre, a cinema, a broadcast station, a hostel, leisure services, training schemes, and support programmes for homeless and disabled people.

As Ceri Cunnington from Cwmni Bro Ffestiniog optimistically remarks: ‘The responsibility for our future lies largely in our own hands. There’s an opportunity in this area to create an environmental, economic, social, cultural and educational future, all based on our cultural heritage. We’ve started to pioneer a way.’

The community in charge

Let’s go back up north, rounding as we must past the rocky fringes of Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon), the highest mountain in the land. In half-an-hour or so we’ll arrive at Penygroes. It’s a small village (population 1,800), but the largest in the Nantlle Valley, where ancient Welsh myths and legends abound.

Like Blaenau Ffestiniog, Penygroes grew around the slate-mining industry in the nineteenth century. Like Blaenau Ffestiniog, local people in Penygroes have responded to the post-industrial era by taking matters into their own hands.

Antur Nantlle ("Nantlle Venture") was established 30 years ago. It works on a not-for-profit basis to run projects and attract grants with the sole aim of developing the area economically, environmentally and socially. Today, it manages over 50 work units that employ over 100 people and it’s currently in talks to buy a large chunk of the local industrial estate.

Up on the high street, if we’d only visited a few years ago, the famous old ironmonger would have been lying empty. Actually, it was falling into ruin. Volunteers assembled. They formed a "community benefit society" and astonishingly raised £900,000 to buy and restore the disintegrating building, naming it Yr Orsaf ("The Station"). The former hardware store has been transformed into a café, accommodation, guesthouse, offices and a digital centre for young people. There are also several community projects on site.

A couple of miles down the road in Llandwrog is the Ty’n Llan pub that we visited on our crawl. While up between the slates and the slopes, in the tiny hamlet of Y Fron, there stands a shop, a bunkhouse and a café. You’ve guessed it – the community is once again in charge.

As a county, it seems Gwynedd punches above its weight in this Welsh world of community entrepreneurism. The last official count suggested it had 128 social enterprises within its border (its total population is around 117,000).

Regenerating community traditions

Throughout Wales, a similar pattern emerges. Community pubs, for instance, are to be found in all corners of the nation. In the South Wales valleys, there’s a portfolio of development trusts that operate as social enterprises in a similar manner. There’s a familiar backstory as well. While they mined for slate in the north, the southern valleys were rich in coal.

Owain Wyn is a regeneration consultant based in the historic castle town of Caernarfon. I ask him why this is happening.

‘Very often, it’s a reaction to the closure of a service, or the threat of closure. And it’s either because the original private business failed to attract enough revenue, or it was because the market didn’t address the need. It’s especially true of the foundational economy – care and health services, food, housing, construction, tourism and retail.’

In Wales, a tradition of community enterprise has existed for centuries. Christian chapels can be found in almost every village in the land; these were funded and built by common people. Workers’ institutes, building societies, trade unions and sport clubs have been around since any of you reading this were born. The social reformer, Robert Owen, was a pioneer of the co-operative movement in the early 1800s. And he was Welsh.

What we do know is that throughout Wales, today’s social enterprises are building on this custom in responding to contemporary needs.

Ceri Cunnington, Cwmni Bro FfestiniogThe responsibility for our future lies largely in our own hands. There’s an opportunity in this area to create an environmental, economic, social, cultural and educational future, all based on our cultural heritage. We’ve started to pioneer a way."

Spaces of Hope

Not unlike us, Dr Debbie Humphry, a researcher from Oxford Brookes University who is working on a research project called Spaces of Hope, recently made a whistlestop tour of some of Wales’s most prominent co-operatives.

‘We found that they’d reshaped and regenerated buildings, developed land and public space, revitalised high streets, taken on closed-down schools and community centres, brought in green transport and energy systems and created new cultural, leisure and health hubs. The regeneration of place meant the regeneration of communities and the regeneration of hope.’

Let’s pop back to Yr Heliwr in Nefyn for a quick nightcap. Bleddyn Evans is still behind the bar to serve us.

‘The high street in Nefyn had become quite bleak and the pub was on the market. "Why don't we try to buy the local pub", we thought. Things have gone from strength to strength. There's no doubt that this is the way forward for every village.’