I went to art college, but I'm an engineer by trade

My earliest passion was painting and sculpture, but I spent my working life as an engineer. Art and engineering aren't so different - look at Leonardo da Vinci. A good industrial design is based on visual principles as well as purely functional ones. And cider is a whole new aesthetic. I shut my engineering company down in 2012, so making cider is a kind of retirement hobby.

We sell everything we produce

There's an absolute natural limit to what this farm can produce, and that's 100,000 litres a year. That's all the juice we can store. The bigger companies buy in syrup and rehydrate it to make cider, but we won't go down that route. We use only apple juice. We try and keep an honesty to our cider. We're a farm on a hill, so our scale of production is pretty much maxed out.

We have eight acres of around 1,200 apple trees

When they're in full production, they'll yield around 30 or 40 tons of apples. But this is basically a hill farm designed for sheep: at 1,000ft there are limitations to what we can grow, so we buy in apples from other local growers. We only use Welsh apples.

I started making cider as a hobby

When we were kids my brother and I made home-brew and hedgerow wine. Over the years you build up a lot of subconscious knowledge. One day a neighbour turned up with half a ton of apples and said, 'We're going to make cider.' So we went up to my workshop and found a big old 10-ton jack that's designed for putting trains back on railways, and we made a press. In the type of engineering I did you become quite resourceful. We ended up with about 80 litres of cider each. At the time I didn't know what good cider was supposed to taste like, but I like it really dry and a little bit sharp, so it ticked all the boxes for me.

We started winning awards – and a hobby became a job

An old friend tried my cider and was raving about it, and together we made some more. Someone suggested we put our cider in a Welsh national competition. It won a prize, so I thought it must be pretty good. Our hobby was becoming a little bit more focused. You build your expertise and bring new things to the party.

We work in a seasonal way

We make our drier ciders with early fruit, and with later fruit we retard the fermentation so we get a bit of sweetness. We age all our single-variety Dabinett apples for over a year, keeping back around 15,000 litres. This is like our crown jewels – we use it to blend with all sorts of different things.

We also age some cider in oak barrels

We use whisky, brandy, rum or sherry casks. Each of them imparts a different flavour to the cider. We don’t want the spirit flavour - just the nuances that interest the drinker. Sometimes these barrels are 100 years old. They may have had madeira in them, then port, then Scotch whisky, and finally we get them. They’ve had an exotic life to say the least.

Blending is a real art

It's like being a painter. You have a palette with three primary colours but can make zillions of colours from those, and all those little nuances make the final product. It comes from the soul. It's an art-form in a way, it's like anything - if you want to get good you've got to practice.

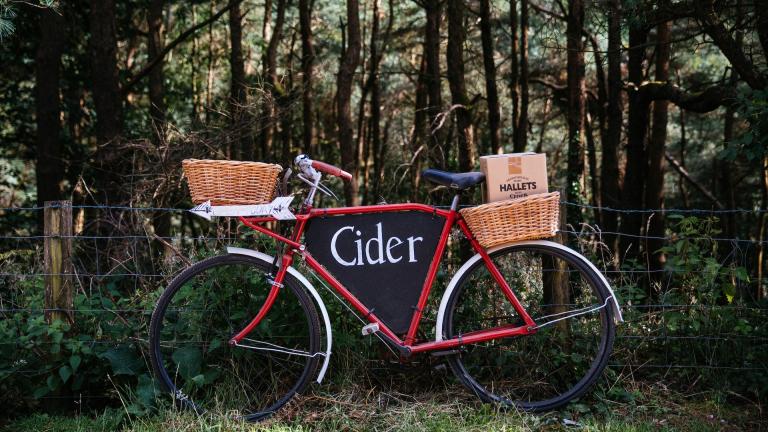

Our branding looks simple, but we've thought a lot about it

I think the rosy-apple-tree-farmhouse motif is exhausted in the cider industry. We thought, let's put something into the market that people want to be seen with. It's deliberately high-end. Our production scales are so small and genuinely artisan, we don't have the luxury of volume. And we don't use any overtly Welsh branding, either. No flags or dragons. It says 'Caerphilly' on the back of the bottle, but that's it.

My name is on the bottle – well, kind of…

Why does my name have two Ts, and the cider just one? We were sitting in the agency office, looking at the designs, and we thought, 'It's nearly there, but something's not chirping here.' They took out a T and we said, 'That's it.' You've got to be pragmatic about it. If it doesn't work, you can't be precious. Let it go.

It's up to the next generation to take it forward

If we do grow larger, it'll be an organic change. We have to stay honest. It's taken time to gain the respect we have, and I'd rather be a luxury brand than a supermarket brand. Our boy Andrew joined the business two years ago and he's become a really proficient cider maker. I don't push my style on him, he makes up his own mind. In fact, most of the production last year was done by him. He takes it seriously and does a good job, and it's nice to see succession in the business.